Hello, Dr. Knaul, it’s a great honor to…

“Please, call me Felicia,” she interrupted immediately, her warmth cutting through the formality.

Felicia Marie Knaul is one of the world’s most influential voices in cancer care advocacy, a leader who doesn’t rely on formal titles or depend on life-saving treatments from the world’s top clinics to do her work. What she does rely on to inspire her work are real-life stories and lived experience: her own, her father’s as a Holocaust survivor, the children from the streets of Guatemala and Colombia, the patients she meets and their families, and the professionals she has worked alongside in the health sector.

This article is about the life and advocacy of Felicia Marie Knaul, who, after overcoming immense personal challenges, now dedicates herself to helping others survive and live with dignity in the aftermath of their own battles.

I’m a Mix of Different Things…I’m All of These Things

“I’m a mix of different things,” Felicia explains with a humble smile, embracing the complexity of her career. Trained in economics with a PhD from Harvard University, she is an advocate for cancer patients, a researcher, and a mother who has faced her own personal battle with cancer. “I do not usually introduce myself as ‘Professor Knaul,’ or ‘associate of the chancellor and distinguished professor of medicine at UCLA,’ or even ‘president of Tómatelo a Pecho,’” she continues, “I’m all of these things together, and that gives me the chance to use evidence to help make change.”

Dr. Knaul’s work spans various sectors: “I’ve worked in both government and non-governmental organizations, and my research has always focused on making a difference through policy, whether in the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors,” she says.

Her journey into advocacy began at a young age. Growing up with the heavy legacy of a father who survived the Holocaust, Felicia learned early on that the world could be a hostile place, particularly for marginalized communities. “I grew up with an awareness that the world can be unsafe for so many people,” she reflects. “That understanding motivated me to do whatever I could to help make life safer for others, no matter their religion, faith, or ethnicity.”

It was this deep sense of justice that led her to work with street children in Latin America, an undertaking that would lay the foundation for her future endeavors as a researcher and advocate focused on public health.

“It lived with us in my childhood home: the mute cry of the Holocaust that was tattooed on my father’s forearm and marked my family. It was part of my upbringing. That fear had lived with me since I was a little girl of about five. Ever since the night I had woken up, crept down the stairs, and heard my father reading the stories he had written and talking with friends – also Holocaust survivors – about his experiences in the Nazi labor and concentration camps.

When I was a small child, my cartoon-like nightmares were about Nazi witches. In these nightmares, I always tried to save my father, to rescue him from the concentration camp, while desperately attempting not to be captured and imprisoned myself.”

From “Beauty Without the Breast”, the book authored by Felicia Marie Knau

Those Who Shaped Me

Throughout her career, Dr. Knaul has been guided by a constellation of mentors. “There were many along the way,” she notes. “My mom’s life was very different from mine. She didn’t have the opportunities I was fortunate to have when it came to education, but she was an unwavering force—always making it possible for me to pursue my education. Few people have shaped me as deeply as she has,” she states proudly.

One of her key mentors was Amartya Sen, a Harvard University professor and Nobel laureate in economics, whose work on poverty and inequity deeply influenced her perspective on economics. “I was incredibly fortunate to have Professor Sen as my mentor at Harvard, along with several other wonderful individuals. What inspired me most was his profound vision of why and how we could address poverty and inequality, and his guidance continues to resonate with me today,” she says.

Her academic journey was also shaped by Albert Berry, a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, who convinced her that economics could be a path to make a difference, even when she initially aspired to become a doctor. “I wanted to be a doctor, but I quickly realized organic chemistry was not my strength,” she laughs. “Albert helped me see that economics could also be a powerful way to drive meaningful change.”

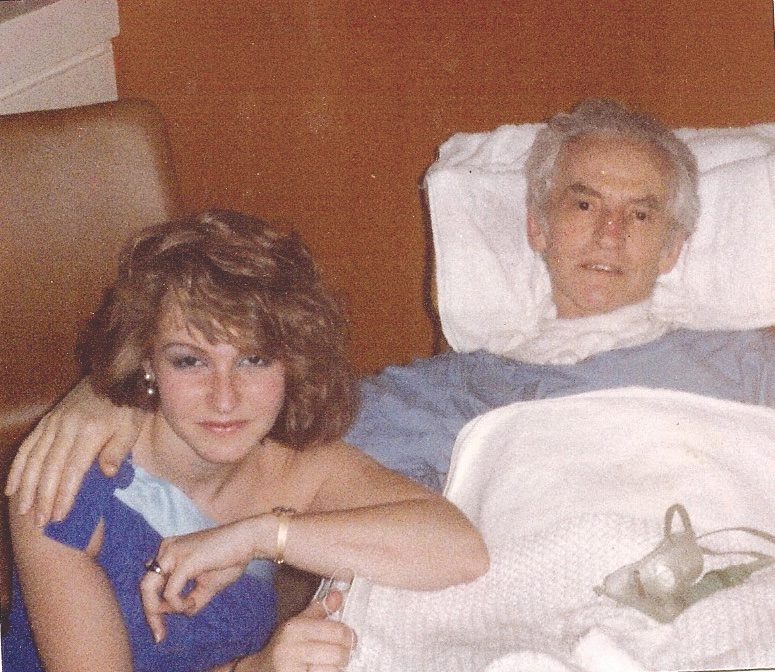

Another formative influence was the late Rabbi Dow Marmur, the senior rabbi at her synagogue in Toronto, who helped her navigate many challenges and career decisions. “Rabbi Marmur was an incredibly inspiring Jewish leader who thought about the suffering of all people, and what we can do about it. He was open, non-judgmental, encouraging, supportive, and he helped me in so many ways, especially after my father passed away from cancer, just after I turned 18,” she shares.

She also speaks proudly and with a sense of loss of the women who have inspired her throughout her journey. Renata Block, a social worker who supported her and her father as he battled cancer, became a close friend and guide as she struggled to identify a pathway for herself rooted in social justice.

Felicia’s work in Mexico was greatly influenced by Sor María Suárez, a nun and a leading figure in the professionalization of nursing in Mexico. “She was one of my closest friends and a huge inspiration,” Felicia reflects. Our friendship began while working together to guarantee access to education for hospitalized children, but evolved into two journeys with breast cancer that only Felicia would survive.

I’m an Atypical Economist… In Many Ways

Dr. Knaul doesn’t fit the mold of a typical economist. For her, economics isn’t primarily about mathematics or numbers; it’s about people. While most economists focus on analyzing how people and countries with wealth choose to spend their money, she centers her attention on those who live without the luxury of choices. She focuses on the people who struggle daily to survive and meet basic needs, with little or no ability to make choices, because they don’t have enough money to make any.

The passion driving her work is rooted in a deeply personal history. “I started my career working with street children, specifically in Guatemala,” Felicia shares. “I am the child of a concentration camp survivor. My father was interned in several camps, including Auschwitz-Birkenau, from the age of 15 to 20, and my grandparents and most of my family were murdered. Almost everyone.” This painful family history fueled her determination to change the world for the most vulnerable, particularly children forced into labor.

But as her career progressed, a new chapter awaited. A move to Colombia to undertake her doctoral dissertation research on street and working children marked a pivotal turning point. There, Felicia became immersed in the country’s health reform efforts, a challenge that would redefine her path and lead her to focus on healthcare, eventually becoming a key advocate for cancer care. “When the health reform called Ley 100 started, and I was offered a position with the Colombian government, the equivalent of the Ministry of Finance, it was an incredible opportunity to learn, grow, and actually be part of something so impactful,” she says.

For Felicia, her involvement in health reform fulfilled a deeply personal longing. “It helped satisfy my unmet desire to work in health care and make sure that people had access to health care,” she admits.

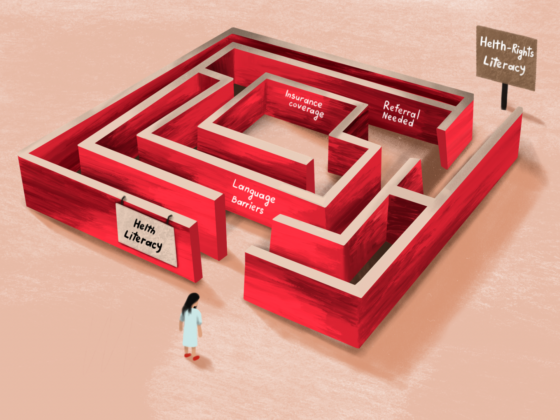

The Idea That Income Determines Access is Unacceptable to Me

As she transitioned into cancer care advocacy, Felicia’s approach was shaped by her strong belief in universal access to healthcare. “I simply can’t accept, perhaps partly because I’m Canadian, that income should determine whether someone receives healthcare, for cancer or for any other health condition,” she asserts. “I believe very fundamentally that access to high-quality healthcare and medicine is a right. The idea that survival depends on income is just unacceptable to me.”Felicia’s most recent work, co-chairing The Lancet Commission on Cancer and Health Systems, has allowed her to push for structural changes in healthcare systems worldwide. “There are ways to make this possible in our world,” she explains, “and with stronger and better health systems that are more thoughtful, we can get exactly what we want: more and better economic growth, with and through better access to healthcare.”

Listen to Their Suffering and Act

Knaul’s approach to global health is defined by a commitment to action, as well as research to generate the evidence to guide that action. “I’m probably unable to design something like a controlled experiment or a pilot initiative that doesn’t involve actually stepping in and doing something,” she admits. For Felicia, encountering a need in public health is a moral obligation. “When you do global health and witness suffering, you’re morally obligated to act, and the research objectives may become secondary,” she insists.

Her unwavering belief in action is deeply personal, shaped by the painful memory of her father’s final days. Despite being in Toronto with full access to care, in 1984, Felicia was unable to secure the pain medication her father so desperately needed. “I had to request the pain medication over and over and then administer it myself the night before he passed,” she recalls. “For years, I wondered: What would I have done if they hadn’t given me that medication? I knew I had done the right thing, but there was also a lingering fear that I had done something wrong.”

That experience became a turning point, driving her to advocate for global access to palliative care. “Even in Toronto, where there was access, I couldn’t get access,” she reflects. “That moment haunted me for decades and continues to shape my work.”

Felicia’s focus on empathy over detachment guides her approach. “What moves me is listening to people, whether it’s a patient or their family,” she explains. “Listening to their suffering, being with them in their homes, and watching how they cope with a dying child or a child with long-term care needs, those real-life encounters teach me far more than reading thousands of articles ever could.”

Felicia not only studies the problems; she embraces lived experience and responds through action. Her commitment to global health is rooted in the belief that real change comes from more than observing, but from stepping in and making a difference.

Breast Cancer Gave Me a Voice

It was her own diagnosis with breast cancer that solidified Felicia’s commitment to cancer advocacy. “Before my diagnosis, I was a researcher. I didn’t walk the talk,” she admits. “Afterwards, I could speak with authenticity. It gave me a voice.”

Choosing to receive most of her treatment in Mexico rather than the United States or Canada was an important decision, she says.“Living with the disease in Mexico publicly gave me the voice I needed to push for change,” she reflects. “I knew that while I had the choice to go elsewhere for treatment, most women don’t have that luxury. I wanted to demonstrate that high-quality care is available in Mexico, and that Mexican women and their families don’t need to go bankrupt to access treatment.”

Felicia’s experience as a patient changed her perspective on cancer care. “Cancer isn’t just about survival; it’s about the long road of survivorship,” she explains. “Policymakers need to understand that cancer patients are not just fighting for their lives, they are fighting for the opportunity to live their lives to the fullest and to thrive.” Felicia, advocacy means building a system that supports patients through every stage of their journey, from diagnosis to long-term care.

Her journey through cancer not only shaped her professional mission but also led her to a deeper, more empowered self-awareness.

“In my mirror, I see a stronger woman than the one I used to see.” “And I like the woman reflected in that mirror,” I added to myself, without uttering the words out loud. “I like myself more than I did before the cancer.

From the “Beauty Without the Breast” book authored by Felicia Knaul

A Triumph of Advocacy and Lasting Impact

When asked about a moment in her career she considers a personal and professional triumph, Dr. Knaul said proudly: “One of my most significant triumphs came with the founding of an NGO in Mexico, which continues to operate successfully today. Tómatelo a Pecho, AC was officially founded in 2011, but began its work on breast cancer in 2008. To have been able to establish and lead an organization that matches research with advocacy and policy is a truly special combination. It’s small but mighty, providing us the chance to project our research into tangible change.”

Her passion for making lasting, systemic changes is evident in her pride over another major initiative: the Sigamos Aprendiendo en el Hospital program. Felicia helped establish schools in every tertiary hospital in Mexico, ensuring that children undergoing treatment, including cancer patients, had access to education. “We were able to legally guarantee children in hospitals the right to education, including those battling cancer, burns, organ transplants and others,” she says. “It still continues today, and I’m incredibly proud to see it entrenched in the Mexican health and education systems.”Two books she authored, Closing the Cancer Divide and Beauty Without the Breast, also stand as pillars of her career. “When I look at those books, I see more than just words on pages,” she reflects. “That’s actually an enduring legacy.”

Looking ahead, Felicia is focused on two critical global health initiatives in her work on cancer control: reducing violence against women that exacerbates cancer outcomes and developing an economics of hope framework, which would demonstrate the broader benefits of investing in cancer care systems. She firmly believes that improving and extending cancer care will save lives and also boost the economy by keeping people out of poverty and ensuring they live long and healthy lives.

She also advocates for a more integrated approach to health advocacy. “We need to stop thinking about health in silos,” she insists. “If we advocate for breast cancer, we should be advocating for women’s health as a whole. Cancer is just one piece of the puzzle.”

Felicia’s legacy will undoubtedly leave a lasting impact on the world of public health, but it is her deep empathy for patients and her relentless drive to bring about change that sets her apart as a trailblazer in cancer care.

As the conversation winds down, Felicia reflects on the impact of her work. “We need to create a world where health is a right, not a privilege,” she concludes. “If we can break down the barriers and globalize healthcare markets, we’ll be able to drive down costs and improve access for all.”

Blitz Round: Who is Felicia Knaul?

Personal Motto or Quote You Live By?

There are many, but one I live by is by Elie Wiesel: ‘In the face of suffering, one has no right to turn away, not to see.’ That’s what drives me every day.

Favorite City?

Paris or Lisbon. But the place that has truly wowed me is Guatemala, particularly the more remote regions.

Most Used App on Your Phone?

Sadly, it’s probably WhatsApp. It’s much faster than texting or anything else.

Favorite Book and Movie?

‘Born Free’ is my favorite movie. It might surprise you, but it’s a classic about freedom and life. As for books, I’m fascinated by ‘The Covenant of Water’ and ‘Cutting for Stone.’

Best Piece of Advice You Ever Received?

If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when? A quote from Abba Hillel.

One Thing People Would Be Surprised to Learn About You?

I love to crochet and do needlework, though I don’t have much time for it these days. And, I also horseback ride!

Comfort Food?

I don’t have just one comfort food, but I do love fruit, muffins, coffee, and sometimes popcorn. And yes, sadly, I adore red meat, especially bison.

Most inspiring person you’ve met in oncology?

Mary Gospodarowicz, former Medical Director at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Canada, Julie Gralow, the Chief Medical Officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, the Executive Vice President, Chair of the Department of Global Pediatric Medicine, and Director of St. Jude Global at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

If a Biography Were Written About Your Life, What Would the Title Be?

A Wandering Jew. Or maybe, ‘The Wondering Jew.’