“Cigarettes are shit.” The slogan is neither creative nor informative, yet it had an impact beyond all expectations in Poland in 1994. These were the early days of post-communism: tobacco companies were making the most of the opportunities of the free market, but people were feeling the rebellious power of the street. The slogan appeared on a still-celebrated poster designed by Andrzej Pągowski, which showed a cartoon-style illustration of a boy in a baseball cap, with a bottom instead of a face, and a cigarette held between the two buttocks.

It was the first time such provocative language and imagery had been used in the context of an official public health campaign. It marked a radical break with the tone of previous campaigns, which had led, for instance, with images of child saying “Daddy, mummy don’t smoke next to me.” Prominently displayed on billboards and bus stops, the ‘cigarettes are shit’ campaign had the intended shock value.

It also played very effectively to an important target population, identifying anti-smoking as ‘cool’, which will have been further strengthened by expressions of outrage from certain quarters. During a Parliamentary Committee hearing, one Member of Parliament suggested Pągowski must have psychological problems. The Minister of Health, however, embraced the new approach, announcing at a press conference, “Ladies and gentlemen, I really don’t understand what the fuss is about; we all know deep down that cigarettes are shit.”

The impact of Poland’s anti-tobacco activities in this period, both at a health promotion and legislative level, won it international accolades. Poland became an example of best practice for new members of the EU, and prompted EU-wide action on compulsory large health warnings on tobacco products.

Hitting the right note

The high impact achieved with such provocative language has, however, been hard to replicate in subsequent cancer awareness campaigns. Szymon Chrostowski, who set up the cancer advocacy foundation Wygrajmy Zdrowie (Let’s Win Health) during his own treatment for testicular cancer, highlights as a particular fiasco a campaign aimed at reducing hesitancy to undergo rectal examination as part of screening for prostate cancer. The campaign used crude language and graphics, which urologists – the specialists with long experience of encouraging men to undergo such examinations – felt actually deterred men from getting screened. Though neither Chrostowski nor his foundation had anything to do with that campaign, as an advocate with a strong focus on men’s cancers, he says he felt somewhat tainted by the whole episode.

Aleksandra Rudnicka, a former spokesperson for the Polish Coalition of Oncology Patients, wonders whether these sorts of campaigns, which seem designed more to shock than to educate, are driven by the logic of social media, where ‘success’ is measured by the number of likes, and can also translate into sponsorship. It’s a particular issue with campaigns aimed at younger audiences she feels: “I don’t understand why people working for PR agencies or NGOs are convinced that only such forms of communication will allow them to reach young people.”

Metaphors, associations and ambiguities, can all play a role, because they catch the public imagination and can be entertaining

Getting the language right does require advanced communications skills, particularly when the goal is to get people thinking and talking about body parts or functions that are considered intimate or embarrassing. Metaphors, associations and ambiguities, can all play a role, say language experts, because they catch the public imagination and can be entertaining and intriguing. Research published in Metaphor and Symbol, in 2021, on ‘Engaging Consumers in a Sexual Health Campaign through the Use of Creative (Metaphorical) Double Entendres’ is an example of the academic discourse that has developed around this topic.

Reliance on these linguistic ‘tricks’ means that some of the more successful slogans can be impossible to effectively translate into other languages. A current example from Poland is the slogan “Nie miej tego gdzieś”, used for a highly successful campaign being run by the digestive cancers patient advocacy group EuropaColon Polska.

To native Polish speakers, this phrase has double meaning: “Don’t ignore something – keep it in mind” and also “don’t hide anything up your backside”. It was a bit cheeky, but also clever and to the point. The doctors were happy to support it and collaborate in various ways, including in presenting information videos.

Getting the message across

Iga Rawicka, president of the EuropaColon Polska, and chief architect of that campaign, believes that involving doctors in getting across key messages on prevention and early detection is important to give authority to information they are trying to convey. She admits, however, that it can be tricky to find ways to combine striking the entertaining, witty, irreverent note that can catch people’s attention with getting across key health messages from trusted sources.

The solution she hit upon in the case of the organisation’s first ever awareness campaign around pancreatic cancer, was to make something funny out of the reality that most people have no idea where their pancreas is or what it does. They produced a series of short ‘detective story dramas’, investigating the mystery of “Where is the pancreas”, with the help of a clinical oncologist from the Medical University of Warsaw cancer clinic who is ‘questioned’ by a detective, played by an actor well-known for her role in a popular police series. The short dramatic episodes, which were posted on YouTube two years ago, continue to attract attention. The concept of focusing messaging about pancreatic cancer around a ‘first step’ of building an understanding about what the pancreas does and where it is was subsequently incorporated into the World Pancreatic Cancer Day advocacy work.

Screenshot: EuropaColon Polski Gdzie jest trzustka? (Where is the pancreas?)

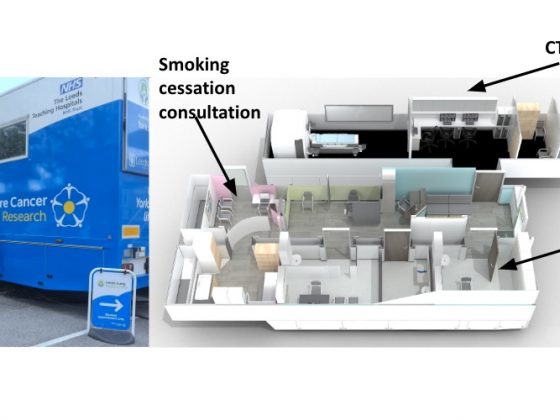

Striking and informative imagery can also be effective in giving people a better grasp of what visible/tangible changes happen when a cancer develops and what that can mean for how it can be prevented or detected in time. As part of its advocacy work, EuropaColon Polski has deployed an inflatable model of a large intestine in public places in more than 20 cities. People can walk through to see what the organ looks like in its healthy state, with an invasive cancer, and in the intermediate state of precancerous polyps.

Jarosław Reguła, a European specialist on colonoscopy for cancer screening, based at the National Cancer Institute in Warsaw, says that, in his experience, these sorts of visual props can be very effective: “I actually met patients who resisted examination, but after entering the intestine, seeing its mucosa from the inside, and being explained how polyps form in this mucosa, they eventually decided to undergo colonoscopy.”

A Healthier Michigan. Republished under Creative Commons licence

The face of celebrities

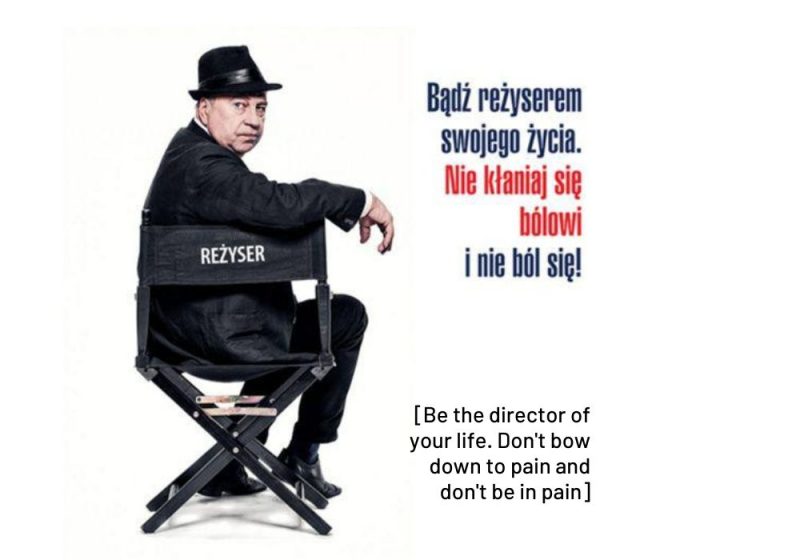

Involving celebrities can be a good way to catch people’s attention, particularly if they are seen to be opening up about difficult things in their own personal experience – though it’s important to avoid offering ammunition to scepticism around publicity stunts. When the Let’s Win Health cancer advocacy foundation ran a campaign encouraging patients to insist on adequate pain control, Chrostowski enlisted the help of Jerzy Stuhr – a very well-known and much-loved actor and director – to be the face of the campaign, which ran under the slogan “Be the director of your life”.

“I simply went through it: cancer, suffering. You’re seeing the face of a person who has struggled with pain”

Stuhr was an obvious choice, as he had been very open about his own experience going through diagnosis and treatment for cancer of the larynx many years earlier, and had even written a book about it. “It was very important to me that the face of the campaign was an authentic person, not just a random TV star,” says Chrostowski. Stuhr also needed to trust that the campaign would not undermine his own credibility as a person who can be trusted to speak openly and honestly: “I simply went through it: cancer, suffering. You’re seeing the face of a person who has struggled with pain,” he says.

The impact of involving celebrities had been evidenced from a previous campaign to promote prostate cancer screening that the Let’s Win Health foundation had run several years earlier. This one involved an actor and a director, in their late 50s/mid-60s, both of them well-known and associated with ‘tough’ roles and action movies, and both living with a prostate cancer diagnosis. Chrostowski says the campaign was effective – in the short-term at least – in encouraging more men to get themselves screened, and reasonate with demographics that public health campaigns can find harder to reach. “No doctor would have persuaded them more effectively,” he says.

Sociologist Tomasz Sobierajski argues that famous male actors who are prepared to step outside their powerful public persona to talk about their own experience of a potentially life-threatening condition are particularly well-placed to convince men to get themselves screened. “Without this personal experience, his message would have fallen on deaf ears. The illness brings him closer to anonymous patients, for whom an inaccessible star becomes so human that it increases the motivation to do the same.”

But that may not work for everyone, says Alicja Stańczuk, who works on educational campaigns for the Blue Butterfly Association, a cancer advocacy organisation focused on ovarian and other gynaecological cancers. “In my opinion, the faces of celebrities and influencers reach more confident and conscious recipients, who know them from Instagram and TV,” she says. She doubts how much impact they have on women in more rural and conservative areas such as those in the countryside around Kraków, where she lives.

“Women in these communities are more likely to listen to their own doctors, who they trust and who know them and their situation”

A cancer survivor herself, Stańczuk argues that TV actresses have done a good job in breaking taboos about cancer in Poland, but says, “When a TV star encourages a mammogram, women react differently: [they think] it’s easy for this well-known woman to see a specialist, but what if they find something in me? how will I cope?” She feels that women in these communities are more likely to listen to their own doctors, who they trust and who know them and their situation, than to a someone famous exhorting them from a billboard to have a mammogram.

The voice of the doctor

That doctors are particularly well placed to deliver prevention/health promotion messages, due to their position of authority and trust, is undoubtedly true. But it is also true that, traditionally, neither they nor policy makers have seen that as their role and responsibility.

Lena Sharp from the Regional Cancer Centre in Stockholm, and past-president of the European Oncology Nursing Society, sees this as a huge missed opportunity. She has been the driving force behind a well-organised initiative – led by the European Oncology Nursing Society, with the European Society for Medical Oncology as a key partner – to show how oncologists and cancer nurses can play a role in delivering prevention messages, particularly to their own patients.

Starting in September 2022, the PrEvCan campaign ran for a year, involving 66 national and international organisations across 22 countries, with the aim of increasing public awareness and – crucially – providing healthcare professionals with a more comprehensive set of tools to effectively communicate the importance of cancer prevention. The prevention/early detection advice codified in the European Code Against Cancer was used as the framework, with one of the 12 recommendations being promoted each month, backed by the supporting scientific evidence. Countries and centres were encouraged to develop their own approaches to carrying out this work, according to their own cultures, traditions and healthcare systems. Participants were encouraged to share what they were doing, and the actions and outcomes of the campaign are now being analysed to draw conclusions about the value of oncology care teams integrating a health promotion/prevention aspect to their work.

Given the growing recognition – including within the Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan – that prevention is not only better than cure, but is the only sustainable option for providing universal access to high-quality cancer care, Sharp believes that including health promotion advice and support within the healthcare delivery pathway is a no-brainer.

She professes to have been somewhat shocked at resistance from European policy makers, who she says turned down previous grant applications for similar projects for promoting prevention, on the grounds that professional oncologists and cancer nurses should not be at the forefront of such activities. “For me, it resembles Stone Age thinking, and I hope we will prove them wrong. Particularly since we oncology doctors and cancer clinical nurses happen to be highly respected in society, and among patients. We are used to talking to people about really difficult issues, such as life and death. People also trust us when it comes to lifestyle changes and prevention.”

“It takes 10 seconds to ask, ‘Do you smoke?’ By not doing so, you give the impression that it is not worth talking about”

Resistance from doctors, she says, often centres around time pressures, which leave no room for talking to patients about the harmful effects of smoking or drinking alcohol. “You really don’t have time for that?” she’ll ask. “It takes 10 seconds to ask, ‘Do you smoke?’ By not doing so, you also leave the patient with the impression that conversations about smoking aren’t important. Which may lead to them not even attempting to quit.”

While six former central and eastern European countries were involved in the campaign, Poland was not among them. But the question of whether doctors in general should take more responsibility for prevention messages has nonetheless arisen in other ways. Rawicka highlights a particular campaign undertaken by EuropaColon Polski that aimed to address delayed diagnosis of colorectal cancer in pregnant women – an issue the advocacy group had become aware of through social media posts. “The aim was to raise awareness… about symptoms and signs that may indicate the onset of colorectal cancer, which they could incorrectly associate with pregnancy itself.”

Obstetricians were happy to collaborate, and gave very positive feedback, recognising that the campaign addressed an important need. But should it be left to advocacy groups to identify and raise awareness around risk factors affecting every woman in their care? “As doctors, we have a very narrow view of our specialities,” commented one of them, “so obstetricians who care for pregnant women do not think about the oncological problems they may face on a daily basis.”

Sharp hopes, and expects, that the strongly positive experience of the PrEvCan campaign will begin to challenge such ‘narrow thinking’, to promote a culture where healthcare providers accept more responsibility for providing their patients with prevention/health promotion information and advice that could be crucially important to their future health.