Cancer is a word no parent ever wants to hear. But when that word comes with no access to treatment, it doesn’t just hurt—it destroys hope.

A year ago, I was walking through a coastal town in Africa. It was a beautiful day—blue skies, warm wind, the smell of cloves and cardamom in the air. Tourists passed by in sandals, drinks in hand, smiling. Then I saw something painted on the wall of a small building:

“X-RAY NOW AVAILABLE.”

Just that. Big letters. An announcement.

I stopped walking. I read it again. In many countries, an X-ray machine is ordinary. It’s not even worth a sign. But here…

Behind the beauty of the island, I saw the gap. I thought of the children—those with persistent fevers, unexplained pain, or swelling that their parents can’t explain. Children who might have leukemia or a brain tumor. Children who don’t just need X-rays, but scans, biopsies, blood work, and most of all, medicines.

Every year, more than 400,000 children are diagnosed with cancer. The vast majority live in low- and middle-income countries. And most of them will die. Not because their cancer is too advanced. Not because we lack the tools to treat them. But because the medicine doesn’t reach them. And it’s worse than it looks: according to a global simulation study published in The Lancet Oncology, estimates that 43% of childhood cancer cases—about 172,000 children each year—go undiagnosed. The burden is overwhelmingly concentrated in low- and middle-income regions.

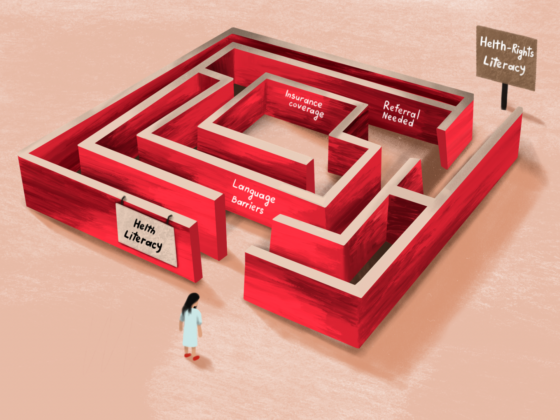

In some high-income countries, progress has been made. Certain childhood cancers now have survival rates over 95 percent. But even there, life-saving medicines are missing from national essential medicine lists. Hospitals may not stock them. Insurance may not cover them. Access is still uneven.

That’s why, on April 15, OncoDaily brought together voices from across the globe for a forum called “Essential Medicines for Children with Cancer: From Access to Action.” It was a call to action. A collective voice rising to say enough is enough. Cancer doesn’t wait. Neither can we.

Right now, the World Health Organization is preparing to decide whether two powerful cancer drugs—Blinatumomab and Temozolomide—will be added to its Model List of Essential Medicines for Children. These drugs are already saving lives in countries where they’re available. Blinatumomab is critical for survival in relapsed or refractory pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and its use is expanding in frontline settings due to its high efficacy and reduced toxicity.

Temozolomide is a standard component in global treatment protocols for high-grade gliomas (e.g., adapted Stuppregimens) and salvage regimens for neuroblastoma and sarcomas. It is included in COG, SIOP Europe, and HIT-HGG protocols and recommended in the WHO GAP-f formulary.

Getting these drugs on the list means more than recognition. It means that the ministries of health will take notice. It means countries will be more likely to include them in budgets and hospitals. It means these drugs could finally reach the children who need them most. In many places, that list is the first step toward access.

It’s a decision that could change the future. And it’s just days away.

But meanwhile, what is being done?

The ACT4Children initiative by Servier, World Child Cancer, Childhood Cancer International (CCI), IDA Foundation, the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) and Resonance, is pushing to close access gaps, in just six months delivering over $2.3 million worth of innovative cancer medicines to childhood cancer centers in Asia and Central America – all at no cost to the families. More than 300 healthcare workers have been trained, as part of a model that brings medicine not in isolation, but with systems, protocols, and human support. Amgen, which makes Blinatumomab, has expanded its access programs, working in close partnership with St. Jude and the WHO to bring the drug to children in India, Pakistan, Vietnam, and beyond. And above all, the Global Platform for Access to Childhood Cancer Medicines—launched by St. Jude and WHO—is quietly rewriting the rules. It is not a donation program. It is a commitment. To ensure that 120,000 children across 50 countries receive a steady, quality-assured supply of life-saving medicines. These are hopeful signs. But they cannot stand alone. They must become the norm, not the exception.

Governments must act. Pediatric cancer must be part of national health strategies. Donors must step in—not just to fund research, but to fund access. And WHO must recognize the urgency of this moment.

Because every day that passes without action is another day when a child somewhere is told, “There is nothing more we can do,” not because that’s true, but because the medicine isn’t there. And in those moments, I’ve realized something painful: for too many kids, it’s not biology that decides who survives cancer. It’s geography.

This should not be our legacy.

We’re not asking for miracles. We’re not demanding the impossible.

This is not just a medical choice. It’s a moral one.

Let’s change that. Let’s make essential medicines truly accessible. Let’s move from talk to action, from policies to patients, from signatures to shipments.

Because every child deserves a chance, not just in theory, not just in speeches, but in real treatment that reaches their bedside.

The time is now.