Should patients be at the centre of attention in the development of new cancer drugs? It might seem extraordinary that this question is even asked – what else matters? But it is a question high on the agenda of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the pan-European non-profit agency, in its campaigning work on ‘treatment optimisation’. It is trying to ensure that the current wave of often very costly drugs are actually used in an optimal way for patients.

The aim is to optimise treatment by answering the many clinical questions not addressed in the traditional development and approval process. As initially set out in a paper co-authored by EORTC director Denis Lacombe (EJC 2017 86:143–9), such questions include:

- How does a new treatment compare with the optimal therapeutic option according to routine clinical practice?

- What are the clinical outcomes when the new treatment is administered in real-life cancer patients or in off-label indications?

- Would it be better to shift the focus to how to combine and/or sequence the new treatment with the existing therapeutic options?

- What is the optimal administration scheme/treatment duration and at which benefit/risk ratio?

- What are patient preferences regarding multiple therapeutic options?

- What are the long-term issues related to the treatment?

The EORTC has been promoting this agenda for several years, including in a 2017 Comment piece Lacombe wrote for Cancer World under the title ‘Let’s be honest, our research efforts centre on drugs not patients’. But it is also a consistent call by leaders across the clinical and patient advocacy cancer community, who have pointed out the neglect in funding academic or public trials that answer such questions.

“We must confirm the data like we do with new cars, which we crash to see if they are as safe as the manufacturers say,” says Lacombe. “Why is medicine the only field where we accept so much uncertainty? There is a big price to pay for uncertainty by driving in the dark and we will encounter big problems such as major toxicity at some point.”

The lack of certainty regarding the risks and benefits of new drugs has increased recently owing to their number and to speedy approvals. American oncologist Vinay Prasad is among the voices who have been sounding the alarm about the design and reporting of registrational clinical trials, and of current regulatory approaches. In his new book, Malignant, he contends that, in an era where surrogate markers are used for approvals, the two factors that matter most to patients – overall survival and quality of life – are being sidelined in many registrational studies and not followed up after approval. “Whether cancer drugs must show survival or quality of life gains before approval is debatable,” he writes, “but no sensible person can think they should never show these gains.”

Greater backing for change in Europe is now in train following the publication of a treatment optimisation manifesto by EORTC and a number of stakeholders, including the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and the European Patient Forum. It was presented last year at a workshop hosted by the European Parliament’s Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA) panel, which had the aim of exploring how a framework for applied clinical research could close the uncertainty gaps generated by the existing system, especially in the era of personalised medicine.

“Why is medicine the only field where we accept so much uncertainty?”

Driving in the dark

As participants at the STOA event heard, ‘driving in the dark’ hampers efforts to focus healthcare spending on treatments that can make a real difference, and avoid wasting limited resources on treatments that offer minimal or no benefit. Wim Goettsch, a health technology assessment specialist at the National Health Care Institute in the Netherlands, who spoke at the event, points out that cancer is a particular concern, as oncology drugs typically have the biggest impact on budgets, and need to show they deliver value for money. The issue of cost and value is becoming more acute because of the escalation in the number of treatments used in managing the disease. “We have focused in the past on single agents, but now there are more combinations and treatment lines, so they end up being more costly in use than you might expect,” he says.

“We see expensive new treatments such as CAR-T being used in practice earlier than say the third line that it is supposed to be used at, and also such treatments are used with other costly procedures such as bone marrow transplants,” he adds. “And people can have treatments again when they relapse, so costs can be higher still. We need to look much more carefully at clinical practice as a result.”

The key question is, what changes can realistically be made to give decision makers more direction on cost-effective practice. Previously, Cancer World has looked at the concept of real-world data – and how far it can be relied on to define the true benefit derived from treatments administered in clinical practice. There are a number of platforms in Europe and the US that are gathering such data, together with initiatives to improve data quality of cancer registries. There has also been progress in grading the value patients get from treatments, such as with the Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale developed by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

But the EORTC takes the view that the uncertainties are just too great to be solved with mining data. They argue for the need to ramp up so-called ‘pragmatic’ clinical trials ‒ trials designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in real-life conditions of routine practice.

The case for pragmatic trials

The idea of pragmatic trials is widespread in medicine, not just oncology. A simple definition is that they “are run in real-world settings, test interventions compared with usual care (rather than placebo), and are conducted in a way that seeks to enhance the generalisability of the results that they produce” (Haff N et al, JAMA Netw Open 2018). There are tools such as the Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary 2 (PRECIS-2) that show whether a trial meets pragmatic ideals. But they can be hard to conduct and face challenges such as dropouts.

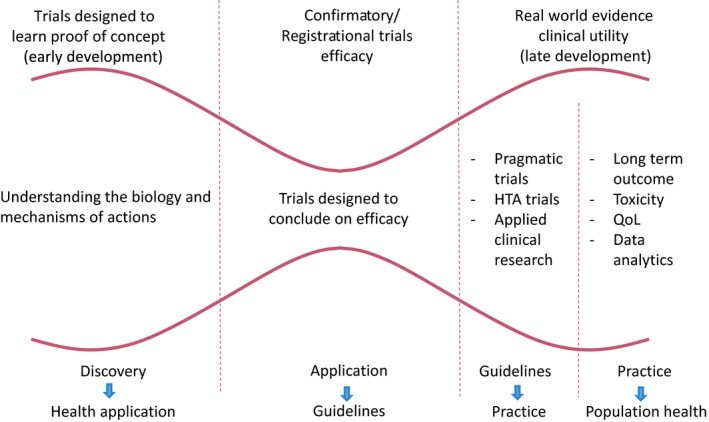

In oncology, the emphasis on optimising treatment mainly concerns new agents in what is more broadly defined as applied clinical research (and in the context of personalised or precision treatments). Lacombe and colleagues put forward a lengthy discussion in a paper last year on the policy changes needed to create a continuum from basic biology to long-term population outcomes, in which an applied/pragmatic trial stage is a fundamental step, and not only for drugs but also for other oncology interventions (Lacombe D et al, Mol Oncol 2019).

A framework for clinical development of new drugs

As examples of the type of applied optimisation work needed, the paper mentions two randomised clinical trials, supported by independent funders, that have been examining optimal treatment duration of immunotherapies in melanoma. The examples are well chosen, as the lack of clarity about how to use these expensive therapies to best effect has been a concern for oncologists, patients and payers. New immunotherapies and BRAF inhibitors prompted a group in the Netherlands to establish the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry, and immunotherapies are also a subject for iPAAC, the third European Joint Action on Cancer (2018-2021) in its work package on innovative cancer therapies, as they “reflect the many challenges faced regarding the proper use of cancer drugs”.

While much of the concern is about new agents there are examples of long-standing oncology practice that were eventually shown to be not effective and even harmful, as timely follow-up trials were not done. A well-known case was intensive chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for breast cancer, which was shown to have increased toxicity with no greater survival, but only after many thousands of women received it.

While much of the concern is about new agents there are examples of long-standing oncology practice that were eventually shown to be not effective and even harmful

Another example was a strategy for managing advanced ovarian cancer with platinum-based drugs adopted in the late 1990s. Thanks to an independent validation trial published in 2017, oncologists now know that a protocol administered as a standard of care to many women did not extend overall survival, had significantly shorter progression-free survival and scored worse in quality of life.

The role of such applied research extends widely in oncology, and not only to new agents, but the worry is that as latest treatments enter use they too may be found wanting after a long time.

Building consensus on the way forward

Since publishing the manifesto, the EORTC and STOA have engaged with stakeholders such as health technology agencies (HTAs), regulators, clinicians and patient advocates on how this could work.

A survey by STOA asks questions such as:

- How should such research be financed?

- Could it run in parallel with classical registrational trials, or only after marketing authorisation?

- How would regulatory agencies use the data?

Interviewees were asked about the current situation, what the features of treatment optimisation studies could be, and how they could be accepted.

Reporting on the findings of the survey, Lacombe and colleagues describe the dominance of drug-centred registrational trials that are not primarily designed to inform clinical practice and do not provide the information doctors and patients need. The report also makes reference to studies showing that, several years after getting market access, a majority of oncology drugs approved in the US and Europe had no or insignificant evidence of impact on survival. A second stage of trials after approval, if done at all, are usually not pre-planned and involve different actors, with industry rarely interested. Hence the need for a formal programme of pragmatic trials.

Most respondents to the survey agree that current drug development is not sufficiently patient-centred, and that there is insufficient real-world evidence, which ‘severely complicates’ the decision-making of HTA bodies, payers and clinicians. They agree that studies are needed that have fewer inclusion and exclusion criteria than the classical clinical trial, and employ the standard of care or the best available alternative treatments as comparators.

There is no such consensus on the optimal timing of studies, however, nor on whether such trials would need to be randomised.

Importantly, the survey showed broad backing for regulatory measures to support treatment optimisation. Views on who should fund treatment optimisation studies were largely split between the option of funding by academic and non-profit organisations or by consortiums of all stakeholders. A combination of public and private funding is seen as most feasible.

The survey showed broad backing for regulatory measures to support treatment optimisation

Asked for pluses and minuses, respondents mention, on the plus side, the use of clinically relevant outcome measures, cost savings, rewarding treatments that add clinical value, and more accurate prediction of real world side-effects. But there are questions about who will foot the bill, the lack of a framework for such studies, reluctance of clinicians and industry to take part, and potential ethical and legal issues.

Three policy options for how treatment optimisation studies could fit within existing regulatory pathways are on the table:

- Making treatment optimisation studies part of the requirements that manufacturers have to satisfy to obtain a marketing authorisation

- Including such studies as part of industry’s post-authorisation commitments

- Using conditional reimbursement mechanisms to compel makers to carry out treatment optimisation studies.

Regulatory perspective

In March 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) published its regulatory science strategy for the next five years. The document addresses many of the challenges that are raised in the EORTC manifesto and work of the STOA panel. Guido Rasi, the EMA’s executive director, accepts that cutting edge treatments such as CAR-T cell therapy raise fundamental questions about how they are assessed and valued. Speaking at the STOA event, Rasi mentioned the concept of ‘evidence by design’, recognising that new types of studies need to be planned, and requirements for post-licensing evidence generation specified, such as what data is collected by cancer registries. Rasi said he envisages a ‘rolling review’ of evidence revision, and essentially a new role for regulators ‘at the crossroads between science and healthcare systems’, acting as a ‘catalyst’ to enable translational research that fits into the reality of healthcare systems.

Rasi envisages a ‘rolling review’ of evidence revision, and essentially a new role for regulators ‘at the crossroads between science and healthcare systems’

The new strategy puts forward a lot of initiatives, and indicates a willingness to engage with the clinical optimisation agenda, but as yet has few hard facts. Among the promises are

- Developing a methodology to incorporate clinical care data sources in regulatory decision-making

- Providing guidance on the roles of patient preferences in therapeutic contexts and regulatory decisions

- Ensuring the evidence needed by HTAs and payers is incorporated early in drug development plans, including requirements for post-licensing evidence generation.

The strategy also calls for the EMA to pilot a system for rapid analysis of real-world data (including electronic health records) to support decision-making at the EMA’s authorisation and risk committees, and generally there is much emphasis on this tier of evidence at European level. While real-world data can include pragmatic trials, projects such as the European Health Data and Evidence Network (EHDEN), launched at the end of 2018 within the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), aims to harmonise 100 million, anonymised health records across multiple data sources, and ties in with other IMI projects such as Big Data for Better Outcomes (BD4BO). (See also the EU Horizon 2020 project, HTx – this has funding of close to €10 million and aims to resolve the effectiveness of complex treatments at HTA level.)

Indeed, a paper by authors from the EMA and other agencies puts forward the idea of a ‘learning healthcare system’, based on electronic health records and other routinely collected data – which in oncology will be the “only hope” to get to grips with the complexities of combinatorial therapeutic strategies, they argue (Eichler H-G et al, Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019). See also a recent paper on new analytic methods using real world data and also cross-trial data from completed randomised trials (Eichler H-G et al, Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020).

Can Europe lead the way?

Pressure to give timely guidelines to oncologists faced with many new agents is only going to increase, as was well articulated by Maurie Markman from Cancer Treatment Centers of America in Philadelphia, in a short MedScape piece, Defining standard of care in oncology. Focusing on his own speciality of ovarian cancer, he says that platinum-based therapy was unchanged for many years, but a number of new options including angiogenesis inhibitors and PARP inhibitors have recently become available. What is the optimal strategy among these different agents? Will there be trials that compare one strategy to another or even several strategies to each other? This falls into pragmatic trials arena, he adds, but there is no simple answer to defining optimal patient management – the standard of care – when ‘very exciting’ strategies are entering the scene on an almost daily basis.

Lacombe considers that the sheer unsustainability of the current system – its huge costs and waste – will force change. He does not pretend to have all the answers, which is why the EORTC brought the multistakeholder treatment optimisation initiative to the European Parliament. But proposing what amounts to a big and potentially very costly new tier of research, and extensive collaboration around Europe on both research and data collection, will need a lot of discussion.

A steer has come from EU health ministers, who have been briefed on improving evidence of patient benefit, and increasing information exchange between regulators and national authorities, and have said that convergence is in the interests of EU citizens. And in that lies the challenge of the European project itself – with the UK now gone, the opportunity for Europe to lead the world in this and other aspects of technology may be getting harder to achieve, but nowhere else globally is likely to have both the capacity and the political will to attempt such a mission.

1 comment

Comments are closed.