This article is from 2022, if you are interested in topics related to the elimination of HPV cancer you can also read:

- Cervical cancer elimination efforts boosted by simpler ways to identify and treat pre-cancerous lesions

- Global elimination: securing a future free from cervical cancer

- Harald zur Hausen: the virologist who opened a pathway to eliminating cervical cancer

Instead, for HPV vaccination and screening policies in the world we have also written:

- HPV vaccination: generating demand by spreading knowledge and information

- HPV vaccination set to be rolled out across Turkey… with controversial exclusions

- Delivering cervical cancer screening across India: the plan… and the practice

- Hospice caring for women with cervical cancer launches own mobile screening clinic

- From stigma to strategy: Egypt’s journey in combating cervical cancer

In rural Romania, in a small town called Sadova, some 200 km west of the country’s capital Bucharest, the local community is trying to ensure that their daughters don’t have to live in dread of cervical cancer.

Sadova is an unlikely success story in what is an otherwise struggling vaccination campaign ‒ an oasis of vaccination in a region where vaccine hesitancy is taking firm root. Out of 66 teenage girls registered at the local medical practice, 60 have received an anti-HPV vaccine ‒ a huge percentage, considering that only around 1% of Romanian teenage girls are currently estimated to be vaccinated.

At the heart of this local success story is doctor Gindrovel Dumitra, who has succeeded in earning the trust of his patients.

“We trust our doctor, we’ve followed his recommendations every time,” says one of Dumitra’s patients, whose 13-year-old daughter has been vaccinated against HPV. “We know that the vaccine offers protection against cervical cancer,” she tells me at the doctor’s surgery.

Of course, like any mother, she was concerned; she wanted to ensure there would be no side effects or problems caused by the vaccine. “I was indeed afraid,” the mother says. “But after the first discussion [with Dumitra], my fears vanished. My daughter wasn’t afraid at all,” she adds.

“We’re still re-earning people’s trust… This is why we talk to mothers about HPV vaccination, even when they come for other problems”

In Romania, as in the rest of the world, trust is an integral part of any successful vaccination campaign, and people are more inclined to trust their doctor than politicians or other authorities, Dumitra says. But it’s a long process. In Dumitra’s clinic, patients come in for various different health problems, but they also come for another reason: they’re looking for his advice.

“We’re still in the stage where we’re re-earning people’s trust,” the doctor says. “A lot of parents are still searching for an infusion of trust. This is the reason why we talk to mothers [about HPV vaccination], even when they come for other problems.”

Whenever a parent comes by his practice, he always tries to drop in a word or two about HPV vaccination. The approach that seems to work best is to explain the benefits of vaccinations in ways that are simple and to-the-point. Cervical cancer tends to be an invisible problem in the community, so sometimes the doctor mentions problems that people can relate to more easily, like genital warts. But while cervical cancer may not be that visible, it takes a major toll. Globally, an estimated 604,237 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2020, and it is the most common cancer among young women in several parts of the world ‒ including Romania. In 2020, 1,805 lives were lost to cervical cancer in Romania. These are all preventable tragedies, says Dumitra.

“Every year, we lose more than 1,700 women. We’re talking about women aged 25 to 65 ‒ young women who are mothers, who have children, who are leaving a family behind,” the doctor says.

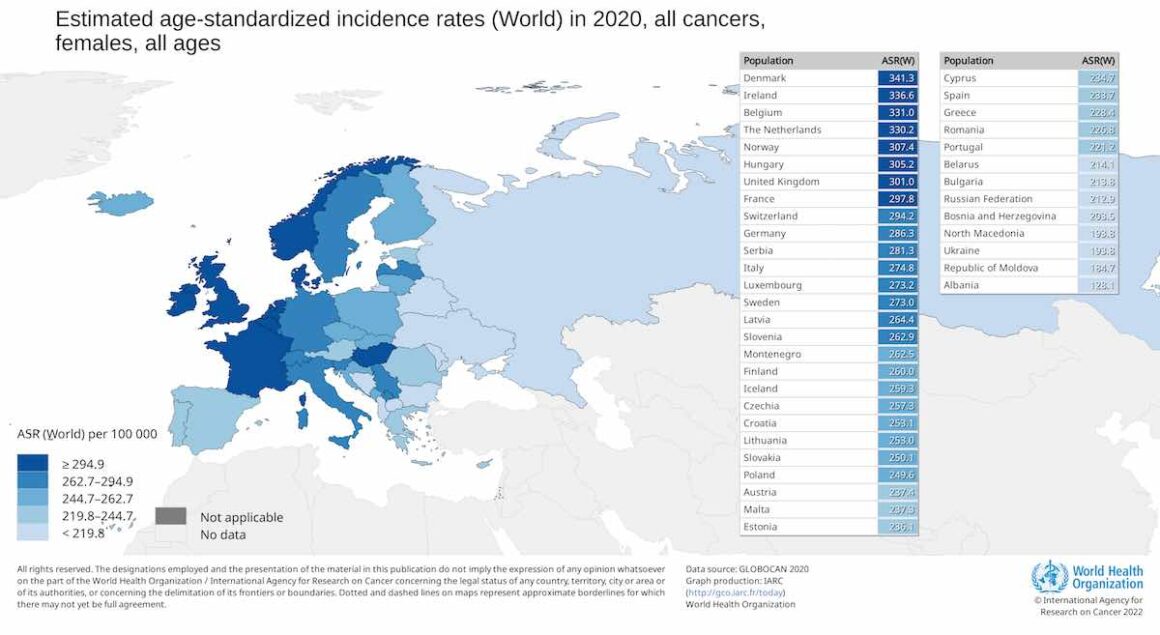

Source: Data source GLOBOCAN 2020; graphic courtesy of World Health Organization (http://gco.iarc.fr/today)

Cervical cancer is one of the few types of cancer that can be directly prevented. In over 90% of all cases, it is caused by HPV ‒ the human papillomavirus, which has several high-risk cancerous strains, and several strains that cause warts. The virus is almost ubiquitous. The odds that an unvaccinated woman acquires this virus is around 85% (US data), and most infections happen at early ages, between 15 and 23 years old, through sexual contact.

The good news is there are several safe and effective vaccines that can protect against this virus, and consequently, against this type of cancer. But a vaccine can only help you if you take it.

The vaccine works and is safe, but myths persist

Romania has the highest cervical cancer incidence and mortality rate in Europe, with up to 17 in every 100,000 women killed by the disease ‒ more than four times the EU average. To make matters worse, the cervical cancer screening rate in Romania is also one of the lowest on the continent. While other countries like Australia and the UK are well on their way to eradicating cervical cancer, Romania is taking wobbly steps towards a proper HPV vaccination campaign.

“Indeed, uptake and acceptance in eastern European countries is not always at the high rates we would hope for,” says Paul Bloem, Technical Officer in the Immunisation, Vaccines and Biologicals Department at the World Health Organization, “and this is of concern particularly because the region does have relatively high cervical cancer incidence.” As he adds, there are many factors at play here ‒ not all of them particularly related to HPV vaccines.

Concerns about potential side effects and that the vaccine could somehow push girls to start their sex life earlier dominated the discourse

Romania started its first HPV vaccination campaign in 2008 ‒ one of the first countries to do so. But the campaign was a fiasco. Just 2% of Romania’s teenage girls got vaccinated, and the campaign was dropped. Back then, concerns about potential vaccine side effects and worries that the vaccine could somehow push girls to start their sex life earlier dominated the national discourse, and authorities were inefficient at pushing back against these myths. Now, we have more than a decade of additional data saying the HPV vaccines are safe and effective but myths persist.

In fact, over the Covid-19 pandemic, “vaccine hesitancy has normalised” and has become a “reasonable position” in Romania, says Simona-Nicoleta Vulpe, a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Bucharest.

“The decision to get the vaccine depends a lot on trust,” says Vulpe. “People get vaccinated when they trust one or more entities that encourage vaccination ‒ whether it’s doctors, experts, public authorities, media, or just people they know.”

Trust and empathy are also crucial tools, according to gynaecologist Alina Diaconu, from the Renașterea Foundation in Bucharest. Diaconu has participated in several Pap smear screening campaigns and also recommends vaccination to her patients. She says there’s a lot of disruptive noise coming from the public sphere.

“During a consultation it takes a lot of time to just take away the baggage of information coming from social media, Google, and other similar sources. Only after that can I tell the patient what’s going on and actually start the consultation.”

“Trust is an ‘essential element’ of any vaccination campaign, and trust requires empathy, expertise, and time”

Although HPV vaccines have been shown to prevent around 90% of cervical cancers (as well as 90% of anal cancers, 70% of oropharyngeal cancers, and 60% of penile cancers), the success of a vaccination campaign hinges on the ability of authorities and doctors to communicate these benefits against baseless concerns. The extent to which public doubt can hinder a vaccination campaign has been shown not just in the case of the HPV vaccine in 2008, but also in the Covid-19 pandemic: in Romania, despite wide availability, less than half the population is Covid vaccinated. As Dumitra emphasises, trust is an ‘essential element’ of any vaccination campaign, and trust requires empathy, expertise, and time.

But trust alone can’t build a vaccination campaign.

Can Romania’s new vaccination campaign succeed?

Romania’s 2008 vaccination campaign failed due to lack of money as well as inefficient communication. But this time around, there are some encouraging signs.

After distributing 40,000 doses in 2021, the Ministry of Health has expanded the campaign to 195,000 doses, for which there is already a demand. Officials are also investigating the possibility of vaccinating boys ‒ an assessment and decision on that “will be coming” the ministry says.

But the doses coming into the country will be enough to vaccinate fewer than 100,000 people. For a country with over one million teenage girls, this is hardly enough.

Because of insufficient doses, HPV vaccination was mostly restricted to well-off families that could afford to buy the vaccine themselves. The price of a dose is now over €120 ‒ girls under 15 need two doses, while girls over 15 need three doses.

“Romania has a sort of à la carte menu for the few parents that understand the importance of HPV vaccination”

Government stocks have been insufficient and unreliable, says Ana Măiță, head of the ‘Mothers for mothers’ (Mame pentru Mame) NGO, which focuses on the health of women and mothers. Currently, parents wanting to vaccinate their girls first need to fill out a form and send it to their family doctor. These forms are then centralised and ordered based on their submission date, and every three months the doctor asks the Ministry for the required doses. It’s a cumbersome and inefficient process, says Măiță, and particularly problematic for vulnerable families.

“Romania doesn’t have an anti-HPV vaccination programme,” she says. “Romania has a sort of à la carte menu for the few parents that understand the importance of HPV vaccination. I’m fighting so we have a true vaccination programme, but Romanian officials haven’t yet set any clear goals as the EU recommends.”

“I often come across situations where parents want the vaccine but don’t have access to it,” she adds.

The goals set by the EU are those recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO): vaccinating 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030 and organising screening programmes to include 70% of women of all ages. Romanian officials have stopped short of accepting these figures as clear targets, but they say they’re working on it.

“The Ministry is considering implementing a sustainable vaccination programme against HPV, aligned with the goals set out in the Europe Beating Cancer Plan, which includes vaccination of 90% of the target population of teenage girls,” one official explained.

Ironically, the biggest roadblock for the campaign is money – it’s ironic because Romania, like every other country, has every financial reason to invest in this type of prevention. According to studies, for every dollar invested in anti-HPV vaccination, a country saves $20‒$50 in the long term; immunised people tend to be healthier, are at lower risk of hospitalisation for HPV-associated problems, live longer, and are active in the workforce longer. Basically, countries can save a lot of money while also offering girls and women a better, healthier life.

Even the country’s National Cancer Plan overlooks prevention, focusing instead on therapy and treatments

Unfortunately, many countries invest too little in preventing diseases ‒ and this is exactly the case in Romania. Romanian authorities haven’t purchased enough doses and haven’t invested nearly enough to bring HPV vaccination into the public eye of the general population. Even the country’s National Cancer Plan overlooks prevention, focusing instead on therapy and treatments. Unsurprisingly, this also means that most people are unaware of cancer prevention methods such as HPV vaccination.

According to a regional GfK study carried out in 2016, two out of three women in Romania haven’t even heard of the HPV infection, and 1 in 10 women have not attended any screening in the past ten years. Just one in four have had a Pap smear in the past three years.

Romania needs a “paradigm change regarding women’s health,” says endocrinologist and former Health Minister Ioana Mihăilă, who was one of the pioneers of the country’s new HPV vaccination campaign. It was during Mihăilă’s term that free vaccination was extended to girls aged 18.

“Anti-HPV vaccination is the best method to prevent cervical cancer, which is why we’ve extended the age group so that more at-risk people can receive a free vaccine,” Mihăilă said, announcing the move in September 2021.

Like all doctors we’ve interviewed, she also wants boys eventually to be vaccinated. Although girls are most at risk from HPV, boys can also develop some HPV-caused cancers and can help spread the virus. At the moment, Romanian parents who want to vaccinate their teenage boys have only one choice, which is to buy the expensive vaccine (assuming they can even find it in stock).

Common problems

Romania’s setbacks are shared by many other countries. While in countries like the UK and Australia, vaccination campaigns have been successful and have led to plummeting cervical cancer rates, others have not been as successful. Denmark, Ireland, the USA and Japan are just some of the countries that have had unsuccessful campaigns in the past.

Part of this can be traced back to insufficient communication efforts.

“With hindsight, one can also say that vaccination programmes often underestimated that this vaccine – given the target of girls of this age – needs much more and sustained communication and sensitisation efforts over several years to be accepted by the population. The normal, tested ways of introducing childhood vaccines may have been insufficient,” notes the WHO’s Bloem. In this day and age, no vaccination campaign can succeed without an adequate communication campaign behind it.

“Efforts have to be based on the latest communication insights, using a plethora of channels to reach people where they are, including digital media, and need to target girls and parents as well as health workers, teachers, and other community stakeholders,” he says.

The good news for countries looking to kickstart anti-HPV vaccination and prevent cervical cancer is that they can draw inspiration from countries that have had success.

Alexander Wright, Global Lead at Cancer Research UK, points to evidence showing the HPV vaccine programme in the UK is now delivering on the hoped for results. “We are very pleased that the positive impact of the HPV vaccination programme is now being seen. This year, a study we funded in England showed the vaccine dramatically reduced cervical cancer rates by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at age 12 to 13.”

There are not many differences between the strategies deployed in developed and developing countries, Bloem explains. The main difference is that higher-income countries tend to have more schools that can play a role in such programmes but tend to have more vaccine hesitancy, whereas, in lower-income countries, vaccination is more often well-received, although developing countries may find it challenging to support the costs of a national campaign.

“It takes political courage to take on preventive health policies… We must do it, even if it means challenging the disinformation channels”

Mihăilă believes that drawing lessons from other countries will be key, especially when it comes to making long-term plans. Any plan must of course be tailored to the local cultural and logistical challenges, but some things are universal: one of these things, the former minister says, is the courage to take on such campaigns even if they may be unpopular with some parts of society. Even in the context of strong vaccine hesitancy currently shaping up in Romania, taking on HPV vaccination has never been more important.

“I think we’ve lacked the courage,” Mihăilă says. “It takes political courage to take on preventive health policies, but these are the most impactful and sustainable policies in the mid and long-term. We have to take them on, even if it means challenging the disinformation channels.”

A roadmap for eradicating cervical cancer

Romania, like many other countries, has wasted over a decade in which it could have tackled cervical cancer. But things may be looking up. Dumitra, the architect of one of the early HPV vaccination success stories in Romania, says that even though the previous campaign failed, he now sees some steps being taken in the right direction, and a window of opportunity may be opening up.

“We’re on an upward trend when it comes to parents accepting the HPV campaign,” the doctor says.

Although cervical cancer is typically caused by high-risk HPV strains, vaccination also protects against genital warts, which are typically caused by low-risk HPV strains.

“Most patients know someone who had a wart and had to cauterise it or do some form of treatment,” says Dumitra. Being able to relate to parents is essential, and this includes considering the concerns expressed by patients, the doctor notes.

The vaccine works best if it is administered before commencing sexual activity. In Romania, this means an average of 17 years for boys and 18 years for girls. While people in their 20s and above are also likely to benefit from vaccination (Australia recommends the vaccine for females aged 9–45 and males aged 9–26), the priority should be focusing on the early teens.

According to Peter Sasieni, Professor of Cancer Prevention at King’s College London, and co-author of the study analysing the success of HPV vaccination in the UK, “The best age to vaccinate girls is 11 to 13, but the vaccine is still very effective at preventing infection at older ages.” There are two issues with vaccinating older teenagers in many countries, he says, “One is that the highest uptake rates have been seen in school-based programmes and, as people age, it is much harder to achieve very high population coverage. The other is that many 18-year-olds will have already been infected with HPV before being offered the vaccine, and once infected (with a particular HPV type) the vaccine offers little or no protection against persistent infection or progression to cancer. Hence whilst individuals in their late teens and 20s may benefit from HPV vaccination, I do not see it as a public health priority.”

The UK’s strategy, well documented by now, shows a roadmap that can be implemented in other places as well. The country introduced vaccination in 2008 for girls aged 11‒13, and then extended it up to girls aged 18. They then moved on to boys aged 11‒13, and females up to 25 years old ‒ a strategy that Romania may also be moving towards.

This can be done step by step and patient by patient, Dumitra believes. But it won’t be easy. From political challenges to financing and disinformation, the logistics of the vaccination campaign are bound to be difficult. But the results will be worth it. As we’ve clearly seen already, we have a vaccine that could essentially eradicate one type of cancer ‒ an achievement well worth the effort.

“HPV vaccination campaigns are critical for the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem,” Sasieni concludes. “If we could vaccinate 90% of girls globally by the age of 15, we would be well on the way to ensuring that cervical cancer becomes a rare disease in future generations.”

This article was written for publication in Romanian magazine ZME Science, with a Romanian language version to be published on the online news service Digi24. It was funded by the European School of Oncology through its Cancer Journalist Grant scheme. © Andrei Mihai