Between 2015 and 2020, age-standardised prostate cancer mortality rates rose by an estimated 18% in Poland, reflecting an increase in deaths from 4,876 to 5,748 over that period. This trend was in sharp contrast to EU countries as a whole, where prostate cancer mortality rates fell by an estimated 7.1% during that time.

This worrying difference was highlighted in an Annals of Oncology article that looked at recent cancer mortality trends in Europe across the six largest EU member states – Germany, UK, France, Spain, Italy and Poland – with a focus on prostate cancer.

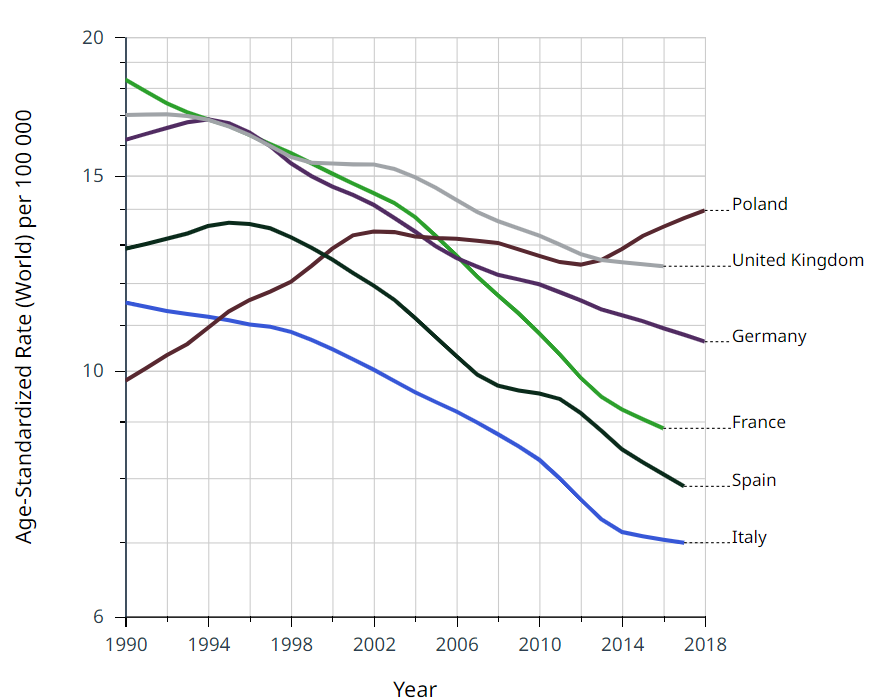

Trends in prostate cancer mortality for the six largest countries in Europe

Source: Globocan. Cancer Over time. International Agency for Research on Cancer – All Rights Reserved 2024 – Data version: 1.0

The authors noted that “Poland is the only major European country not showing favourable trends and prediction in prostate cancer [mortality] rates.” They also pointed to a pattern of “smaller and later declines in mortality trends… observed in some Central and Eastern countries,” which they said were “probably partly due to a delayed and limited access to modern effective treatments.”

Could improved access to modern effective treatments provide the solution to halting – and then reversing – Poland’s rising mortality rates for prostate cancer, and if so, is the country on the right track? Or are there other factors at play that need to be recognised and addressed?

Cancerworld put those questions to a wide array of professionals and patient advocates.

A system under pressure

Tadeusz Włodarczyk, a patient advocate and co-founder of Gladiator, a group for men with prostate diseases, has been supporting men with prostate cancer for 20 years, partly via Gladiator’s helpline. He has also been monitoring the decisions of successive policy makers.

Now aged 88, he expressed a certain bitterness. “They don’t really care about the patient,” he says. Almost every caller to the helpline is worried about the long queues to see the doctor.

“I often hear that an appointment is months away. Patients are impatient, they don’t want to wait that long. They get discouraged.”

Getting an appointment with a urologist is easier in big cities, where urgent cases can usually be seen within two to three weeks. In smaller towns such as Łomża (population 62,000), Słupsk (90,000), and Nowy Sącz (83,000), patients may have to wait two to four months, or even longer, to be seen. For patients deemed to be ‘stable’ (meaning non-urgent), the waiting times in those three towns in December 2023, were up to eight or nine months. This may be one reason why many men already have advanced disease by the time they get to see a urologist.

Tomasz Szydełko, National Consultant in Urology and Head of the University Centre of Excellence in Urology at Wrocław Medical University, points to delays with primary care as part of the problem, as access to a urologist always has to come via a general practitioner. “Removing referrals would really make it easier to access the specialist,” he says.

Could “delayed and limited access to modern effective treatments,” also be a factor in worsening mortality rates, as suggested in the Annals of Oncology article? Roman Sosnowski, a urologist at the Maria Curie-Skłodowska Cancer Memorial Hospital in Warsaw, believes lack of availability of treatments for advanced disease during that period could offer a partial explanation, but what worries him far more is a failure of the system to get the many different specialists who play a role in prostate cancer to work together around each patient in a coordinated way.

“Cooperation between urologists [specialised in diseases of the prostate] and clinical oncologists [specialised in cancer medicine] is at a different level in our country than in others,” he says. “Moreover, there are only a few specialised, multidisciplinary departments dealing with comprehensive treatment of prostate cancer.”

“It must be due to the system… The cancer care system in Poland is at its limit. I really mean it”

Piotr Wysocki, Head of the Department of Medical Oncology at the Jagiellonian University-Medical College Hospital in Kraków, also voices scepticism over how far Poland’s worrying trajectory on prostate cancer mortality can be attributed to delayed access to new treatments. He acknowledges that in the period looked at by the Annals of Oncology article, namely 2015–2020, novel prostate cancer drugs became accessible more widely in Western EU countries than in Poland. However, he says this cannot explain why Poland’s mortality rate is rising.

A former President of the Polish Society of Clinical Oncology, Wysocki blames the rising mortality rate on an overloaded cancer care system, which he says is particularly detrimental for those with advanced disease. “If the problem was just a matter of limited access to novel therapies in Poland, the effectiveness of prostate cancer treatment would be constant in Poland while improving in the Western Europe and the USA,” he says. “However, the data shows a clear increase in the mortality rate in Poland.”

“It must be due to the system,” he says. “The cancer care system in Poland is at its limit. I really mean it.”

Too few medical oncologists

This is particularly evident, says Wysocki, in the case of patients with advanced cancer, where, due to significant progress in the efficacy of systemic treatment, many novel drugs have significantly prolonged patients’ overall survival. Many patients with advanced cancer now undergo treatment for years, which puts additional demands on the healthcare system. Many experience adverse, sometimes life-threatening, events which require skilful and competent management.

The shortage of doctors is an acute problem shared by health systems across Europe, as recently highlighted in a Cancerworld article on Tackling the crisis in Europe’s oncology workforce. The situation in Poland, though, is especially critical. “Over the last seven years, the number of patients requiring lifelong systemic cancer treatment in our department has more than doubled,” says Wysocki. In the Department of Oncology at the University Hospital in Kraków – the largest university cancer centre in Poland – there are only 11 medical oncologists handling 57,000 therapeutic or consulting visits every year.

“Patients with prostate cancer are mostly burdened with a number of other conditions… They need to be given much more time”

Quality care needs time, he adds. Patients with advanced prostate cancer are often elderly, and treatment frequently involves relatively new drugs which will have been tested in younger populations. Optimising the treatment plan requires knowledge, experience and skill… and the time to understand the needs of each individual patient and personalise the treatment accordingly. “Patients with prostate cancer are mostly patients burdened with a number of other conditions due to their age. They need to be given much more time,” Wysocki emphasises.

Better therapies – a source of hope

But if lack of access to new treatments for prostate cancer is not the sole culprit for Poland’s rising mortality rates, improved access may yet have an important role to play in helping reverse the direction of travel. The good news is that recent years have seen a significant expansion of access to reimbursed therapies, with some calling it “a real explosion”. Szydełko agrees that, despite bureaucratic delays, more novel drugs are becoming more widely available.

Reimbursed access to cancer drugs in Poland is organised within a framework of so-called drug programmes. These define the set of patients who are eligible for a reimbursed treatment – which may be more restrictive than the indications for which the drug has marketing authorisation. It also specifies the diagnostic tests required to demonstrate eligibility and to monitor treatment. The list is regularly updated, says Szydełko, with new drugs being included and others having their indications extended. A major update took place in March 2023.

A 2023 Europe-wide review of access to drugs for treating metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, and both metastatic and nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, shows that Poland’s National Health Fund does provide access to the majority of the drugs and combinations. Significant exceptions include abiraterone, enzalutamide or apalutamide for patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive disease, though there is access for patients with castration-resistant (non-hormone sensitive) disease. Cabazitaxel and olaparib, both approved for treating metastatic castration-resistant disease (the latter in men with a harmful BRCA mutation) are also shown as not reimbursed in Poland. “It could be better, but it’s not too bad,” Szydełko concludes.

A 2023 Europe-wide review of access to drugs for treating prostate cancer shows Poland does provide access to the majority of them

The quality of surgery is also improving, says Łukasz Nyk, head of urology at the European Health Centre in Otwock, near Warsaw. He cites figures on the increasing use of robot-assisted surgery, which has been reimbursed by the National Health Fund for prostate surgery since April 2022. “Four years ago, there was only one surgical robot in our entire country. Today, after several years of rapid progress in this field of urology, there are about 40 robots. This results in an increase in the availability of modern surgical treatment.”

There are signs that the introduction of robotic surgery and newer therapies could also change Poland’s prostate cancer landscape in other ways. Talking to patients and advocates, there seems to be a growing confidence that modern treatments are not only effective, but also lead to fewer side effects. This may improve rates of early detection, as it reduces fears of getting tested, ‘in case they find something’.

Awareness and early detection

Public information campaigns are also helping to raise awareness of the disease and the importance of getting screened and watching out for suspicious symptoms. “Over 20 years we have distributed thousands of leaflets,” says Włodarczyk of Gladiator. In recent years there have been social media advertising campaigns urging men to get tested, and prostate cancer prevention is now being talked about more and more openly. The ‘Movember‘ campaign, which every November encourages men to grow a moustache to raise awareness around testicular and prostate cancer prevention, has become very popular in Poland.

Issues around prostate cancer are beginning to break through to mainstream media, says Nyk. “I recently saw a spot on TV about prostate cancer and testicular cancer prevention for the first time in my life.” Prevention of breast and cervical cancer have been talked about for a long time, he adds, while cancers that affect men have been overlooked, “This is now changing.” Nyk has also noticed that, as awareness grows that prostate cancer can have a genetic basis, the sons of men who have undergone treatment are now starting to turn up at doctors’ offices.

“I recently saw a spot on TV about prostate cancer and testicular cancer prevention for the first time in my life”

The fact that PSA testing for prostate cancer is available for free under Poland’s ‘Prevention 40 Plus’ programme, should also give a boost to early detection. The programme was introduced in July 2021, but it only has a few more months to run, with a scheduled end date in mid-2024. To date, one million of the 10 million eligible men have taken advantage of it. “We would like every man over 50 to visit a urologist once a year with a PSA test result,” says Szydełko.

Getting Poland back on track

What will it take to stop the rise in mortality from prostate cancer – and then get it onto the downward trend seen elsewhere in Europe?

Invest in the system, says Wysocki, the medical oncologist based at a large university hospital. He sees the systemic problems dogging prostate cancer treatment as merely a prelude to even worse problems that may become apparent in future years, as the increase in cancer patients requiring long-term treatment far outstrips the increase in the clinical oncologists.

Among the recommendations for addressing the workforce crisis, he mentions cutting bureaucracy – which he says consumes large amounts of time that oncologists could otherwise devote to patients – and introducing effective psychological support for oncologists and oncology nurses to avoid professional burnout.

Nyk, the urologist based at the European Health Centre – a leading privately run hospital – says he does see ‘light at the end of the tunnel’, but agrees that “financial outlays are needed”. Tomasz Szydełko, head of urology at a university specialist urology unit, is pinning his hopes on the advances in access to drugs and modern surgery. “We are a bit behind, but we are catching up. We hope to improve the statistics.”

As for the patient advocate Tadeusz Włodarczyk, what gives him hope is a marked change in the mindset of the patients he talks to, and in their level of engagement with their treatment. “I no longer meet patients who think that a diagnosis automatically means the end, each knows that there are treatment options, each already has some knowledge. This is a good change.”