Effective palliative care has become a growing priority in African health services in recent decades. This is partly a result of the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases including cancer – and the sad reality that palliative care is often all that can be offered by way of cancer care, because the diagnosis often comes too late and access to treatment is limited.

There is also a growing recognition within oncology that palliative care can play an important role in patients undergoing curative treatments as well. “Most people understand palliative care as care for the dying,” says Henry Ddungu, consultant in haematology and oncology at the Uganda Cancer Institute. “But the message is to look at it as a strategy to live and have a better quality life… There is evidence to show that those who initiate palliative care early have higher survival rates – ideally at the time of diagnosis.”

Collecting data in palliative care supports improved decision-making and learning, and allows comparisons and the measurement of performance. It can also be used in budgeting and helps those involved to make the case for investment.

Guidance issued by the World Health Organization in 2021, which set out practical approaches to support good policy, strategy and practice in palliative care, stressed the need for countries to use data effectively at district and national care points to ensure quality and equal access, and plan budgets and make the case for investment. Governments work with data, and without it funding becomes a problem.

WHO guidance on practical approaches to support quality palliative care

The 2021 WHO guidance document highlights the importance of:

- Incorporating quality into palliative care planning

- Taking an integrated approach to palliative care across the health system

- Developing robust measurement systems to drive improvement

- Assuring quality palliative care services at a national level

- Committing to palliative care at a district level

- Using data at the district level to improve palliative care

Many African countries report using registers for documenting details of the patient, their diagnosis, the service provided, and use of oral morphine. The data is recorded by palliative care providers and then pushed into a central system for health ministries to analyse and act upon. National co-ordinators have oversight of data submission to make sure providers deliver the data updates on time.

In Kenya, for example, where palliative care is provided by units mainly based in government institutions, and coordinated by the Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association (KEHPCA), data has been collected at 110 KEHPCA sites since 2005.

“The data helps us analyse areas of strength, challenges and policy formulation,” says David Musyoki, KEHPCA Director. It also helps keep track of trends, such as the number of patients using morphine, and with forecasting. “So, at the end of the day we know where the gaps are and can follow up.”

It has taken time, however, to get these data collection systems to where they are now. Ensuring the reporting tools are used in a correct manner with every centre aligned has been one challenge, along with the lack of human and financial resources – it’s always a fight to get overstretched health services to prioritise data.

Uganda: teasing out the hidden data

In Uganda, health establishments at all levels, from local health centres to national referral hospitals, have long been capturing data and sending it to the Ministry of Health. Initially, however, all the data went into one big basket – and separating out palliative care interventions was difficult.

“We could not tease it out,” says Moses Muwanga, assistant health commissioner for palliative care at Uganda’s Ministry of Health. “You’d notice a cancer somewhere, but tracking out palliative care was a big problem.”

To address this problem, the Ministry decided to adopt a specific tool for registering and monitoring palliative care services. This initiative was championed and supported by the Palliative Care Association of Uganda, which recognised the need for data to inform – and make the case for – improvements in the service.

“In our country, the ultimate goal of integrating palliative care data into the HMIS [health management information system] is to generate evidence for decision making,” says Mark Donald Mwesiga, Executive Director, of the Palliative Care Association of Uganda. “In our country access to palliative care is limited because its poorly funded and trained service providers are not fully recognised within government structures. The strongest reason is because the country lacks credible data on the amount of need for palliative care in the country.”

“Having data in the HMIS will generate a strong base for evidence for funding for medicines, training and services in hospitals and the community,” he says.

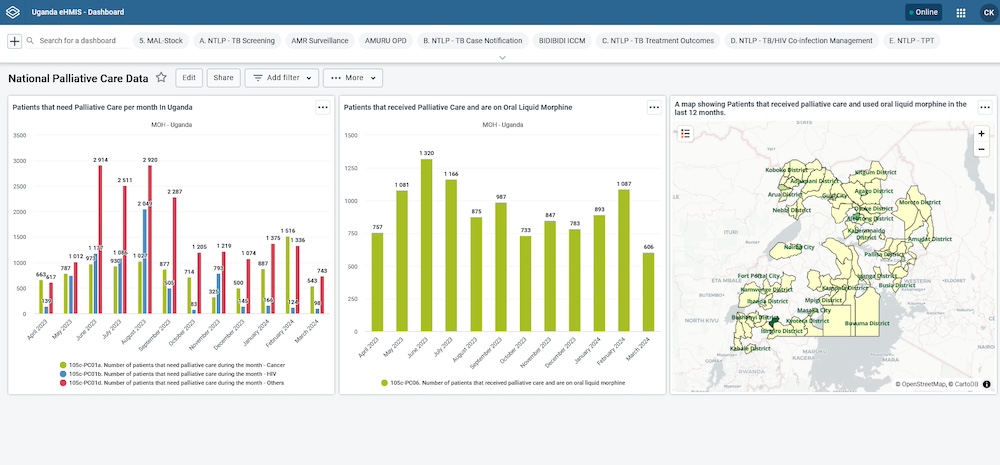

Palliative care data dashboard, Uganda Ministry of Health

Source: Cynthia Kabagambe (2024) Enhancing palliative care data collection nationwide. Published on the website of the Palliative Care Association of Uganda

While some disagreements and misunderstandings on what constitute palliative care remain, the tool allows the Ministry of Health to easily identify for what disease the palliative care was being administered, and to get a longitudinal picture of the progression of the diseases that require palliative care.

“If someone came in initially and came back, it would allow us to know if their condition was progressive,” says Muwanga. The tool records whether the patient’s return was for pain or symptom management, and whether they were taking morphine.

Data on the numbers of people who are consuming oral liquid morphine per month, and for which type of cancer and in which circumstances, helps the Ministry plan ahead to meet national needs. It is also valuable for identifying discrepancies and potential outliers where issues might need to be addressed.

For example, the district of Kabale was found to have a consumption of morphine which far exceeded what would be expected for its population. “We had a meeting and discovered that they were using morphine for other things, like burns and caesarean birth,” says Muwanga. “This was okay, but it was not documented. When they explained and correlated the data, we knew that these are some of the lessons we have to learn.”

Kenya: limited by lack of staff

In Kenya, by contrast, national reporting specifically of palliative care interventions has been in place for almost 20 years, co-ordinated by the Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association. However, many of the 110 healthcare organisations providing palliative care across the country struggle to free up staff to complete the monthly reports, says Musyoki, who estimates that around 80% of providers capture the palliative care data efficiently. The geographically dispersed location of services, he says, means that workforces are isolated, and highly stretched staffing levels make it hard for some centres to set aside time for data reporting. He would like to see responsibilities to submit data being backed by funding to cover the time it takes to carry out that work effectively.

Musyoki would also like to see more investment in statisticians and analysts who could ensure the data collected is used to maximum effect to improve services and inform policy.

Efforts to harmonise the data are made on a continuous basis, says Musyoki, with the whole data collection process subjected to an annual review.

South Africa: limited by lack of priority

South Africa is among the many African countries that now have the tools and ability to report on palliative care. But here too the impact is currently limited, because it is underfunded and not given the attention it needs.

There was a position with specific responsibility for palliative care within the office of the Ministry of Health, but that post has not been renewed for two years now, says René Krause, assistant professor and head of the Division of Interdisciplinary Palliative Care and Medicine at the University of Cape Town. “We have taken it up to the Department of Health, and they are very aware that this is one thing that we are very passionate about, that we need to get that person to coordinate the monitoring and evaluation and implementation of palliative care across South Africa,” she says. “At the moment, there is no official forcing people to report on palliative care.” She worries that, without this, data collection will become ‘a non-issue’.

“We have got a policy which clearly speaks about the monitoring and evaluation of palliative care, but there’s no funding to do that monitoring and evaluation… From an advocacy point of view, how are we enforcing governments to report on palliative care outcomes? We need more advocacy at that level.”

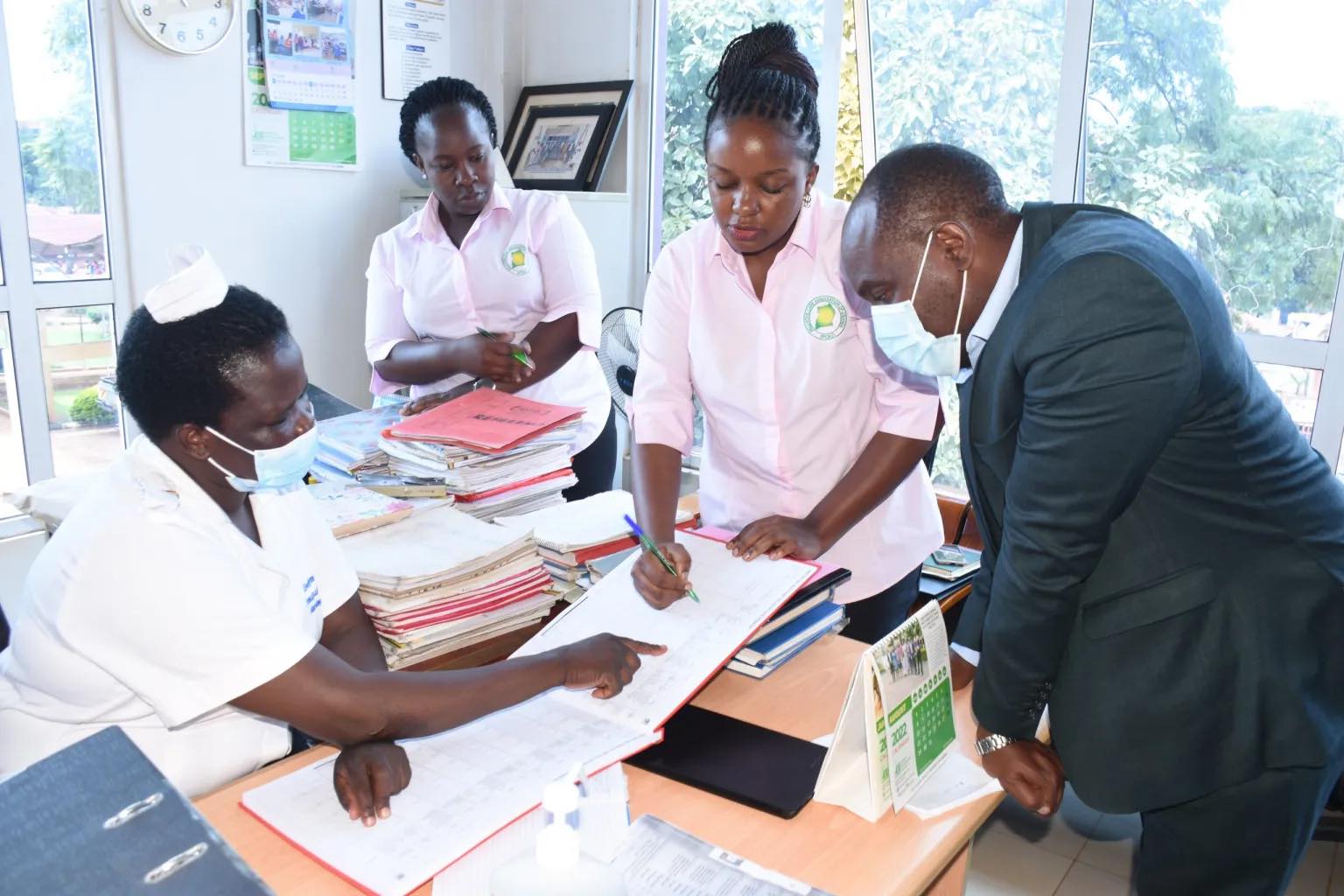

The opening illustration shows Moses Muwanga, the Assistant Commissioner of the Ugandan Ministry of Health Palliative Care and Hospice Services, with staff at the Palliative Care Association of Uganda, as they run a support session on the use of the new data collection tools. Photo credit: Palliative Care Association of Uganda